by CM Meyer

Pumping highly saline wastewater from fracking operations can not only cause earthquakes tens of kilometres away but can also result in increasingly severe earthquakes years after the pumping has ceased.

While this article particularly refers to research on fracking outside of South Africa, these recent findings could have implications for the MeerKAT square array as this, like many proposed fracking activities, is based in the Karoo.

New research - further away

“New research has now linked distant earthquakes to fracking, providing evidence that much larger surrounding sites may be at risk from drilling operations than previously demonstrated.” [2].

Recently published research [7] has shown that injecting fracking fluid or waste salt water from fracking into rocks can cause earthquakes “as far as 50 km away, making it difficult to guarantee the safety of surrounding areas” [2].

The research has also explained this rather strange result. In experiments, the researchers found that pumping water into relatively shallow geological faults caused “rock along the fault lines to slowly slip”. While these movements didn’t cause earthquakes at the point of slippage, they gradually increased pressure on more distant parts of the faults, sometimes causing earthquakes tens of kilometers away from the actual borehole and much further than what the injected fluid could reach [2].

So, adding fracking fluid to rocks can cause earthquakes far beyond the reach of the fluid [5]. Another unsettling finding made recently by other researchers is that, years after fracking fluid or saline wastewater is no longer pumped down a borehole, the earthquakes caused can become bigger [1].

Larger earthquakes?

“Because fluid pressure continues increasing at these depths [8+ km] for over a decade after significant SWD [salt water disposal] rate reductions, our study implies that even though earthquake frequency may decline after reduction of SWD injection rates, the sinking wastewater may induce larger earthquakes” [1].

How is this possible? First, one must understand why earthquakes from fracking occur. Tens or sometimes hundreds of millions of years ago, the areas that contained the gas yielded by fracking were ancient seas. As time went by, silt on the sea floor eventually turned into rock (typically shale) and the organic matter in the silt changed to gas. But, much of the “seas” remained, trapped in pores in the rock along with the gas, and, over time, what was originally sea water absorbed more salts from the surrounding rock, including some radioactive material.

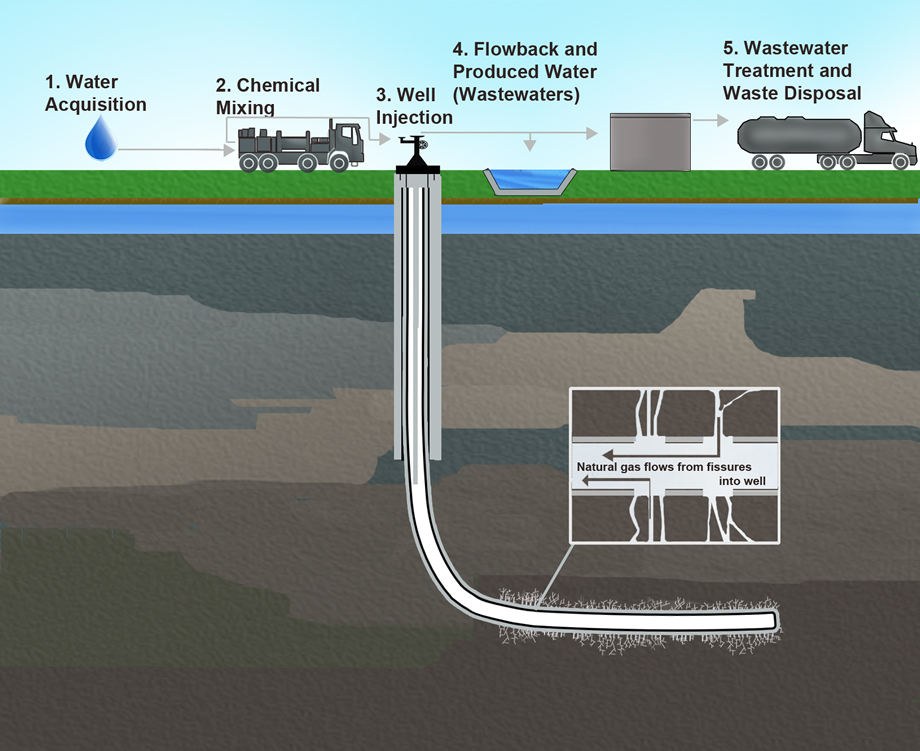

When, millions of years later, a drill bit moves horizontally through the narrow shale deposit and fracking fluid creates cracks around the borehole, the high pressure in the rock is enough to force the gas and salty water up the borehole to the surface (see Figure 1). This scenario would pose a problem of what to do with the wastewater, made of fracking fluid and water from the ancient seas, which cannot be allowed to reach and contaminate ground water deposits.

One solution is to drill a very deep borehole which reaches far below the gas and ground water deposits and pump the wastewater into it. This would create another problem because at these depths (typically 6 km underground), sheer pressure prevents layers of rock and ancient faults from moving. But, when the fracking fluid is forced in under pressure, this starts to act as a lubricant, and the rock, which has been under tremendous stress for millions of years, could start to move to relieve these stresses.

The movement might be slow and gradual, but it could also be sudden and violent, particularly where an ancient fault suddenly releases pent-up stresses. This sudden movement would result in an earthquake. Thus, faults which have been quiet for 300-million years could suddenly start to move dramatically [4].

And, as researchers have recently found, as the mass of salty wastewater sinks slowly down, it can result in deeper faults releasing more energy for a long time. Thus, for more than ten years after pumping of water into a well has ceased, earthquakes could continue to occur, and, as the water moves deeper, the earthquakes could worsen. Eventually, the earthquakes die down and stop but not before massive damage has been done. The strange part is that much of this had been discovered by 1967 and since forgotten.

Old research

“On 10 April 1967, the largest earthquake of the series to that date shook the Denver area. It magnitude was estimated at 5,0 by Maurice Major, on the basis of the Bergen Park Observatory records” [6].

On 8 March 1962, workers from the US Army began pumping hazardous chemical waste down a recently drilled disposal well at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, northeast of Denver, Colorado. The well, some 3671 m deep, then appeared to be an ideal way to dispose of waste fluids from chemical manufacturing operations.

On 24 April 1962, two seismograph stations operating in the Denver area began to record earthquakes. The epicentres of these earthquakes were later located “within a region about 75 km long, 40 km wide, and 45 km deep”. Most of these earthquakes were later found to be within 8 km of the disposal well [6].

In November 1965, a geologist found a direct link between the volume of contaminated waste fluid injected into the well and the earthquakes. Some of the earthquakes registered between 3 and 4 on the Richter scale, which is classed as minor and light. However they were felt over a wide area, and light damage was found near the epicentres [6].

In February 1966, injecting wastewater fluid into the well at Rocky Mountain Arsenal was stopped, because of the suggested link to the earthquakes in the area. However, the earthquakes did not stop, continuing at a rate of “from 4 to 71 per month” [6]. They began to worsen. On 10 April 1967, the largest earthquake so far shook Denver. Then estimated at 5, it was estimated as “moderate”, but caused minor damage over a wide area. After a few aftershocks, it was thought this was the end of the earthquakes. But on 2 August 1967 another large earthquake of “between 5 ¼ and 5 ½” struck the area. It was followed soon afterwards on 26 November 1967 by another earthquake “of magnitude 5,1” [6]. Gradually, the earthquakes petered out, but residents of Denver continued to feel earth tremors until 1981 [3].

Further research

“In 1969 Chevron Oil allowed the USGS [United States Geological Survey] to use one of its wells to more closely study the effects of fluid pressure on faults” [3].

This well, in the Rangely oil reservoir in Colorado, was within a seismically active zone. Chevron had been injecting water into this well to facilitate oil production. By adjusting the pressure of the water, USGS specialists found the precise water pressure necessary to cause earthquakes. Thus, by 1970, strong scientific evidence had emerged linking fluid pumped underground into deep wells to earthquakes.

Forgotten knowledge

“Unfortunately, the lessons of Rangely and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal were apparently forgotten by the early 2000s, when fossil fuel companies embarked on the shale-gas boom” [3].

When similar earthquakes linked to wastewater pumped underground began to emerge in areas of the USA after late 2008 (first in the states of Texas and Oklahoma), it proved surprisingly difficult to link the pumping of fracking fluid underground to the earthquakes. By now, powerful commercial interests were involved: the oil companies which were conducting the fracking, and the state geological authorities who were relying on the fracking boom to provide a much-needed economic stimulus. These parties did not want to be reminded of the lessons learned from Rangely and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal.

Oklahoma waited until 2015 until it began to act after “more than 750 earthquakes over seven years” had occurred [3]. Although the volumes of wastewater injected into wells in Texas have decreased slightly, the state has yet to admit a firm link between fracking and earthquakes. If the recent research findings are correct – and they certainly appear to be, given that they confirm the research findings of Rangely and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal – millions of people in Oklahoma and Texas are at risk of suffering property damage from increasingly severe earthquakes [2].

The future

“The earthquake rate in the state [of Oklahoma] has grown at an astounding pace. In 2013 the state recorded 109 quakes of magnitude 3 [on the Richter scale] and greater. The following year the number jumped to 585, and in 2015 it reached 890” [3].

What are the implications of all this? They can be summed up in two words: not good. If the recent research is correct – and there are considerable indications that it is – then earthquakes from fracking could not only last for more than ten years after fluid injection stops, but also increase in severity, before ultimately fading away.

While this data is not South African, it does indicate that any fracking undertaken in the Karoo – even test wells – could have consequences that were not considered a decade ago.

Besides the potential for wrecking the aquifers that supply Karoo boreholes with life-giving water [9] (now increasingly important to help towns and farms survive droughts), fracking could also cause earthquakes which would affect the Karoo, and cause property damage on farms and in towns. While nobody can say for sure, there are examples of previous seismicity in the Karoo which might possibly be reactivated by fracking fluids [10, 13, 14].

As Chris Hartnady comments, “The southern Karoo lies within the Cape Stress Province, which fringes the second-largest lithospheric stress anomaly on the planet. It is therefore probably far more vulnerable to triggered hydro seismicity than Oklahoma” [11, 12].

And there is something else that needs to be answered: What would the effects of prolonged earthquakes in the Karoo be on the Square Kilometre Array and MeerKAT radio astronomy [8] projects? I suspect the answer would be “not good”.

References

1. RM Pollyea, et al: “High density oilfield wastewater disposal causes deeper, stronger, and more persistent earthquakes”, Nature Communications, (2019) 10:3077, pp 1-10, www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11029-8

2. G Foulger: “Fracking can cause earthquakes tens of kilometres away – new research”, The Conversation, 7 May 2019, pp 1-4 https://theconversation.com/fracking-can-cause-earthquakes-tens-of-kilometres-away-new-research-116539

3. A Kuchment: “Drilling for earthquakes”, Scientific American, Vol.315 No.1 (July 2016), pp 42-49, www.scientificamerican.com/article/drilling-for-earthquakes/

4. A Kuchment: “Drilling reawakens sleeping faults in Texas, leads to earthquakes”, Scientific American, 24 November 2017, www.scientificamerican.com/article/drilling-reawakens-sleeping-faults-in-texas-leads-to-earthquakes/

5. RG Andrews: “Oil drillers’ attempts to avoid earthquakes may make them worse”, Scientific American, 26 September 2018, www.scientificamerican.com/article/oil-drillers-rsquo-attempts-to-avoid-earthquakes-may-make-them-worse/

6. JH Healy, et al: “The Denver earthquakes”, Science, 27 September 1968, Vol.161, No.27 September 1968, Vol.161, No.3848, pp 1301-1310, https://earthquake.usgs.gov/static/lfs/research/induced/Healy-et-al-1968-Science-(New-York-NY).pdf

7. Bahattacharya, et al: “Fluid-induced aseismic faulty slip outpaces pore-filled migration”, Science, 3 May 2019, Vol. 364 No. 6439, pp 464-468.

8. Wikipedia: “Square kilometer array”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Square_Kilometre_Array

9. CM Meyer: “The economics of fracking: Parts 1 -3”, Energize, 9 August 2014, www.ee.co.za/article/economics-fracking-resources-reserves-recovery-efficiency.html; 9 September 2014, www.ee.co.za/article/economics-fracking-resources-reserves-recovery-efficiency-part-two.html; 26 September 2014, www.ee.co.za/article/economics-fracking-resources-reserves-recovery-efficiency-part-three.html

10. M Singh, et al: “Seismotonic models for South Africa: synthesis of Geoscientific information, problems, and the way forward”, Seismological Research Letters, Vol 80 No 1 Jan/Feb 20019, pp 71-79, http://africaarray.psu.edu/publications/pdfs/singh.pdf

11. C Hartnaday: Umvoto Africa, Personal communication.

12. CJH Hartnady and MS Fynn: “Recent triggered (hydro) seismicity in Oklahoma: a cautionary tale?”, GSA South Central Section – 49th Annual Meeting, Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA. 19-20 March 2015,

https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2015SC/webprogram/Handout/Paper254249/Hartna…

13. M Fynn, et al: “Micro-seismic observations in the Karoo: Leeu-Gamka, South Africa”. Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol 18, EGU 2016-12438, 2016 (https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2016/EGU2016-12438.pdf) [Accessed August 2019].

14. M Fynn: M. “Micro-seismic observations in Leeu-Gamka, Karoo, South Africa”, M.Sc. thesis, UCT, 2018, https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/29816

Send your comments to rogerl@nowmedia.co.za